Cricket is a euphony! Beyond the scintillating cover drives and the red cherries nipping in and out, which usually capitulate the attention of the viewer, cricket is pleasing to the ear. It has been made so by a league of extraordinary gentlemen, who have, by their sheer tenacity, created a beautiful concoction of cricket and phonaesthetics. A well-timed cover drive would be incomplete without an accompanying sentence from a commentator expatiating it.

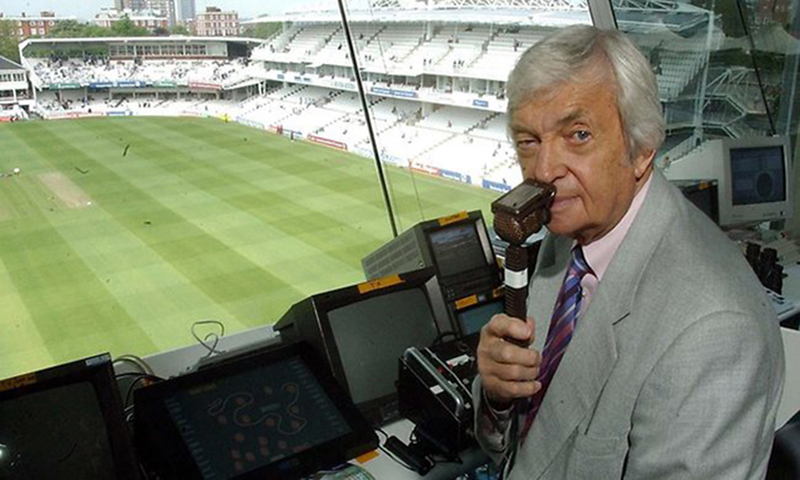

Commentary was first used in 1927, in a first-class match between New Zealand and Essex, on BBC. This was the first time that people were acquainted with ball-by-ball commentary, and the art hasn’t looked back since. It has become an indispensable part of the game. Cricket legends, like Richie Benaud and Tony Greig, took up this art after drawing curtains over their playing days. And it’d be fair to say, they were just as brilliant behind the microphone as they were on the field. John Arlott, Alan McGivlray and Brian Johnston were another few important exponents that helped in increasing the reach of the sport, by giving their voices to cricket.

India, too has had its share of commentators who were pivotal in popularizing the sport across the country.

But the challenges for Indian commentators were more. In a country where the masses enjoyed the game in open ‘maidaans’, it was quite a task to get everyone behind their national team. Though the national team had its own following, it was in local cricket where the country’s heart resided. It was in a local cricket tournament – The Bombay Quadrangular – where India found its first cricketing voice.

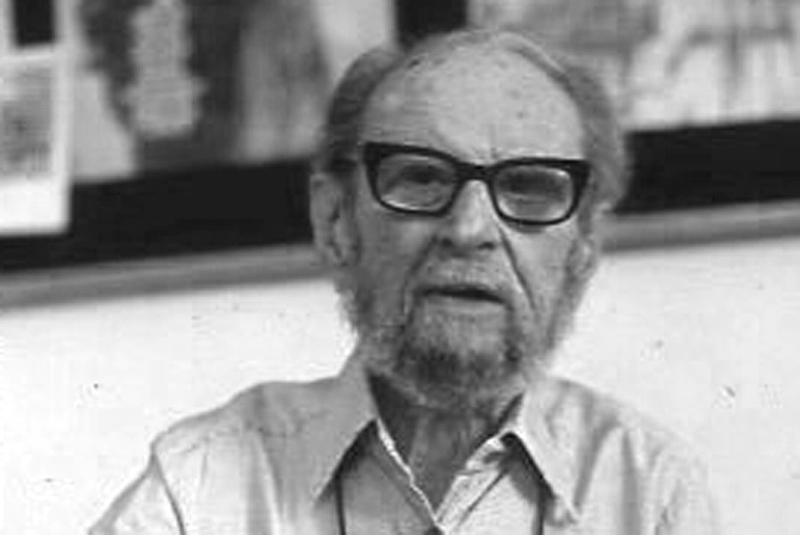

Ardeshir Furdorji Sorhabji Talyarkhan, popularly known as ‘Bobby’, was appointed to commentate during the Bombay Quadrangular in 1934. The Quadrangular, which later became the Pentangular, was a feisty tournament. The teams, based on religious grounds, competed fiercely till the last minute. But, despite criticism from various portions of the country for having teams based on communal grounds, ‘Bobby’ Talyarkhan’s extraordinary exploits behind the mic saw the popularity of the tournament grow. Few of the matches of the tournaments reached a fever pitch across the country. It was not that people liked the idea of teams having players of different religious beliefs being pitted against each other, but it was the cricket and how it was described, which the audience marvelled at.

Eventually, the Bombay Pentangular was abandoned by the Board of Control for Cricket in India in 1946, but ‘Bobby’ Talyarkhan had become the articulate voice of cricket in India by then. He became a regular on All India Radio for all matches played in India. Ramachandra Guha, in his book ‘On the corner of a foreign field’, describes Talyarkhan: “he brought to cricket broadcasting a rich, fruity voice and a fund of anecdotes. He was ambitious and opinionated, with a voice that was beer-soaked, cigarette-stained.”

Another remarkable quality possessed by Talyarkhan was his ability to narrate the game for long hours. He commentated alone for the entire duration of a test match. That makes it 5-6 hours of continuous talking for 5 days in a row. A thought which would be unimaginable for modern-day commentators, who work only in half-hour shifts. Yet, Talyarkhan sailed through the routine effortlessly. He was particularly adamant on commentating alone. He would have it no other way. And due to this, after West Indies tour of India in 1948/49, Talyarkhan parted ways with AIR after they were reluctant to let him commentate alone. He did make brief return stints to commentary but nothing as prolonged and enriching as his first spell. He preferred writing cricket columns, instead.

Despite an early exit, Talyarkhan remains India’s first cricket commentator. He even commentated on other sports broadcasts like Hockey and Cycling. But for cricket, he set a platform which would make Indians embrace the foreign sport of their oppressors with open arms in the years to come.

In the following decade, the baton of Indian commentary passed on to the serene voice of Anant Setalvad. He was the new flagbearer of an art which was meant to enthrall masses larger than ever before, by encapsulating cricket and its minutiae to the eager audiences. Talyarkhan made it reach into the hearts of every Indian, Setalvad had to ensure it stayed. He managed to do that and much more.

Anant Setalvad, born and brought up in Bombay, had himself played as a cricketer for CCI in the 60’s before eventually taking up the trade of cricket commentary. He was a commentator like no other. Where most commentators tried to hype their depiction of an order of play to get their listeners on edge, Setalvad had them hooked with his tranquil baritone. Never did he engage in over-the-top, larger than life description of events. Rather, he was always articulate and concise, providing the listeners with everything required to paint a picture of the events in their heads. Much like Richie Benaud, Setalvad was pleasing to the ear. The listeners simply wanted his melodious speech to go on endlessly.

This was an era when Television was a luxury only a handful could afford, and radio sets were making their ways into the homes of people. Setalvad’s voice reverberated the atmosphere in stadiums into people’s living rooms. It felt as though the entire room transcended onto the ground. Right from the direction of the blowing breeze, to the colour and cracks on the pitch, Setalvad enchanted his listeners with every last detail. His nuanced and astute commentary hardly had any dose of hyperboles or unfunny cracks at humour. He had equally able partners in Dicky Rutnagur and Suresh Saraiya, and the trio had Indian audiences glued to their radio sets, with contributions from former India batsman Vijay Merchant.

Anant Setalvad managed to inspire an entire generation to avidly follow the game and even take up the art of commentary. One of the best of the current lot, Harsha Bhogle, recalled on Setalvad’s sad demise, how he used to imitate Anant: “As a young man, I imagined I was Anant Setalvad and I would try to copy his style but could never get the lilt and authority that his distinguished voice produced. He was always the commentator I wanted to be. The brightest light in the finest era of radio broadcasting in India.”

But, despite Setalvad making great inroads into popularizing the sport, one key aspect was still missing. And in came an 18-year-old from Indore, Sushil Doshi.

All India Radio, in 1968, was looking for a Hindi commentator for its broadcast of the Ranji Trophy. Hindi commentary was an unknown craft at that time. Sushil Doshi, then a college-going student, went for the audition and was initially rejected. It was only when the producer was unable to find anyone else that he decided to give Doshi a chance. This decision turned out to be a landmark for cricket commentary in India. Sushil Doshi’s voice struck a chord with the Indian masses. Within no time, Doshi was commentating side by side Setalvad. A pair of English-Hindi commentators allowed more people to connect with the sport. There was no longer any distinction between listeners. Be it a rich businessman sitting in his office or a rickshaw puller at the side of a road, for the duration of the match, they were simply two ardent cricket lovers who wanted to hear their team play.

Doshi’s imagery and aural abilities were top-notch. Right from the crackle of the ball hitting the middle of the bat, to the thud when it struck a batsman’s pads, Doshi would cover it all. What stood out was Doshi’s intricacy and eye for detail. He would take great efforts to describe the field positions after every couple of overs. For Doshi, it was extremely important to describe the entire process of stroke-making, action by action. He would start from how the bowler was running up to the crease and how the batsman stood, followed by where the delivery was pitched and how the batsman played his stroke. Like a chain reaction. Doshi converted figurative poetry in motion, happening on the field, into actual poetry through his melodious voice and compendious choice of words.

On the other end of the microphone, millions of listeners used to be gelled to their radio sets. With bated breathes, and on the edge of their seats, they followed Doshi’s each and every word. This was Sushil Doshi’s ‘Aankhon Dekha Haal’, which took Indian cricket from the colossal stadiums to the narrow ‘gallis’ of every ‘mohallah’, from the press boxes to the ‘nukad chaiwallas’. Cricket was now a viral fever. It was being discussed at markets, shops, offices and at homes it was a part of dining table conversations. Every match India played was a festival, wherein each and every member of the family had to join and be a part of.

Another big reason for this increase in popularity was that India had started performing consistently. They were winning matches not only at home but abroad as well. The likes of MAK Pataudi, Sunil Gavaskar and Bishan Bedi had found a place in every Indian’s heart, across generations. All India Radio and its commentary teams had been at the centre of this rise and adoration. They gave a first-hand account of it.

But the waves of change hit radio broadcasting hard.

The late 70’s and early 80’s brought the advent of Television broadcast. The famous English commentator John Arlott believed that in radio commentary, the commentator was the hero; the entire focus was on the words of the speaker. With TV coverage, however, the screen was the hero. Vivid description from the commentator was left unpraised when the exact scene was in front of the viewers in motion. It was one of those classic scenarios where a machine had rendered a manual effort useless.

Times changed, broadcast methods changed, and so did the art of narrating events. The modern-day commentators were supposed to play a secondary role. It was no longer about simply describing events, they now had to analyse the performances. They had to make the audience understand why things happen the way they do. There have been ample who have succeeded in this new form. But due to the scope of modern commentary being largely technical, the trade is now dominated by former cricketers. Radio commentary nowadays survives, barely. There are only a handful who still feature in radio broadcasts, Sushil Doshi being one of them, but radio commentary’s time is long gone. It’s magic and aura, though, still afresh in its nostalgia for its listeners, like a dictophone replaying in their hearts.